Fontburn School

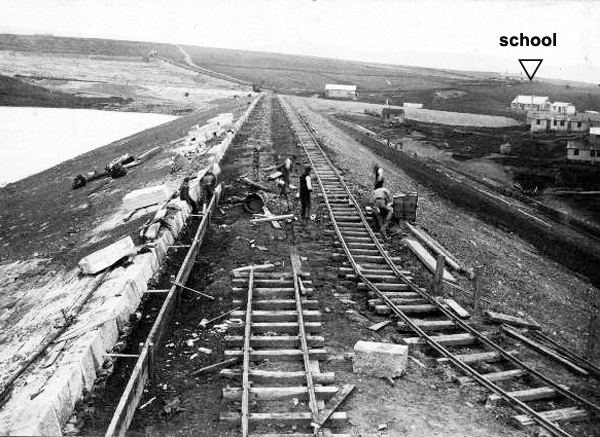

One of the few pictures showing the location and appearance of Fontburn School

(Information drawn from the School Log Book and Inspectors’ Reports is in italics, as are direct quotes from former pupils)

1891 and 1901 Census

The 1891 census shows a school at Coldrife, a farm on the upper edge of the Whitehouse quarries. On the census entry, children living at Whitehouse were listed as ‘scholars’. The logical conclusion is that these scholars went to Coldrife school. It is rumoured that there was also a school at Forest Burn. Apart from the 1891 census entry, no records exist for either case and while every effort was made to encourage school attendance, it was difficult to enforce, especially in rural areas, and ‘school pence’ often a requirement. The next census,1901, makes no mention of a school at Coldrife at all, implying that it had either moved elsewhere or closed. Thus there could have been many local children who had no education at all.

The 1902 Education Act in operation

All this was to be remedied with the arrival of the Waterworks, for by Act of Parliament in 1902, education had been made both free and compulsory for all children aged 5 to 12/ 14years (later 15), to be funded by the rates. County Councils had come into being, and brought with them Education Departments, with legal responsibility to provide schooling where none existed and there was a need. Fontburn had a need.

Built in 1904 and opened to pupils in 1905, ‘Font Waterworks Council School Hollinghill’ was a perfect example of the new Act in action. Fontburn’s catchment area was to include not only the new Fontburn Waterworks community, but also the families of quarry workers who lived at Whitehouse, children of local railway employees, and those from all the farms near and far that came within the scope of ‘nearest school’.

The land on which the school was built was Tynemouth Corporation property, but the building and school house belonged to Northumberland County Council. The school was built to accommodate 100 pupils, 60 in a main room and 40 in an infants room, known affectionately to us as the ‘Big Room’ and the ‘Little Room’. Boys and girls had separate entrances, a place to hang coats, and wash hands - cold water only. Separate toilets were in the playground, of the primitive variety (closet, later Elsanol, and emptied by the caretaker into a pit not too far away) An adjacent schoolhouse was built for the head teacher as was usual in remote rural areas for obvious practical reasons. The caretaker was always someone local who could attend to the lighting of fires as well as cleaning. The first caretaker lived at nearby Bullbush. In 1927 the then current caretaker moved into the schoolhouse, and there remained even when no longer in post. From then on, the head teacher travelled in, first by train, and later by car.

Today there is little trace of the school, and none of the schoolhouse. The brick foundations of the school are still there, though well hidden by rough grass and a wood now stands where the schoolhouse, toilets and latrine pit were. There is no sign of the playground, though an outline of what had been the school garden is still traceable to a knowing eye, and a single brave daffodil was once seen as a reminder and proof of a former existence. The school closed its doors in 1951, with the 17 pupils and furniture and fittings transferred to Rothbury, and the wooden and corrugated iron buildings sold and removed. Nature then took over rapidly to return the site of 46 years of education back into rough pasture.

The first teachers

The school actually opened its doors for business on 17 April 1905, under the headship of one Robert H Rowse. He wrote as his first entry in the school Log: ‘The children are in a very backward condition. There is no possibility of teaching the infants and they are therefore to be sent home until an infant mistress arrives’, adding three weeks later: ‘I find the attainments of the children very varied – some scarcely know their letters. It is very uphill work.’ The school had a hesitant start, with late additions such as ‘pegs for cloakrooms’ and ‘sewing materials and clock arrived’ and ‘fire guards arrived at last’ being noted, as well as the start of what was to be an ongoing dispute between head and caretaker over the lighting and maintenance of the two stoves. Matters improved when the newly appointed Infants teacher began and the official report by a visiting Inspector was very complimentary about the order and discipline, though less so about attainment of ‘children whose education has hitherto been more or less neglected’. Numbers on roll escalated to over 100 within the year, stretching capacity in the Infants’ room to unacceptable limits. Of the 58 infants, all those under the age of 5 were sent home, by order of the Managers.

The School Managers

The Managers’ role was similar to the Governing Body of today’s schools, a group of mainly local people of some standing within the community, and in Fontburn’s case, including the Anglican vicar from Rothbury, all of whom met regularly at the school to offer support to the Head. Willy Stephenson of Newbiggin, Peter Aitchison of Morrel Hirst, Tom Bewick of the Waterworks all put their official signatures into the log book, as confirmation that the attendance registers had been checked and found correct, a quarterly legal requirement. Local people such as my Dad (Tom Bewick) were also very useful for practical matters such as carrying out minor repairs, or offering consultation or reinforcement in times of trouble – such as whether or not to close early because of inclement weather.

Funding

Throughout the first four decades of the school, the average weekly attendance was noted, sometimes with anxiety, by the Head. This was because the annual grant for the upkeep of the school was calculated, not unlike today, per capita, and based on the average attendance for the year. In the early years the annual allowance was 22 shillings for each older pupil and 17 shillings for each infant. This can be compared with c. £2000 per capita today only if we take the changed value of money and average wages into account over the intervening 100 years. Fontburn School’s total grant for 1906 was £108-18s. Regular average attendance returns were made to the County, and an annual inspection by a County Inspector (His Majesty’s Inspector or HMI) was arranged and reported on.

Inspectors’ Reports

Sometimes the reports were glowing and sometimes extremely critical, though usually constructive and understanding of the special circumstances of this remote little school. Attendance often depended on the weather, and frequently children had to be sent home early, especially in snowy, stormy conditions. Some days, when the total head count was so low because of severe weather, special regulations could be cited, allowing attendance recording to be suspended – thus avoiding an unnecessary lowering of the average for the week. At times the school had to be closed, either because of severe weather, or when an epidemic hit, such as diphtheria in 1914 and whooping cough in 1916. Fear of the Spanish Flu in 1918 also kept pupils at home.

1913 school group, loaned by Alison nee McLennan

Click on picture for larger view.

Attendance

Absentees could be chased up by means of the Attendance Officer, or by other means, as in the case of two boys ‘kept at home to break stones to complete a special order at the Quarry. Am calling attention of quarry manager to this.’ Another entry read: ‘Cautioned girls about absenting themselves to help mother.’ The annual Rothbury Races in April took its toll, with a mass evacuation on the midday train, and school attendance falling off so markedly that for several years the Head declared it an official holiday.

1913 school group, loaned by Alison nee McLennan

Click on picture for larger view

Because of the requirement to keep such careful note of attendances, we have a reliable record of the varying size of the school: from its peak in 1906 of 101 pupils, to its gradual decline to 16 in the late 1940s and 17 in 1951 when it was deemed no longer viable to keep the school open. 1908 saw the first decline, marking the finishing of work on the Waterworks and dam, and the moving away of families that had come knowing the temporary nature of their tenancy. As the quarry families gradually left Whitehouse, moving away to other quarries such as the Lee, the roll dipped to an average of 65, then fell steadily through the 1930s until by 1940 it was 19. This became the norm.

1913 school group, loaned by Alison nee McLennan

Click on picture for larger view

School Heads and Assistants

Altogether, seven permanently appointed Heads spanned the life of the school: Mr Rowson 1905 – 08; Mr Cooke 1908 – 14, with a five year interruption for war service, returning as Captain Cooke 1919 – 20; Mr Brewer 1915 – 18, covering the previous Head’s wartime absence; Mr Dixon 1920 – 37; Mr Sayburn 1937 – 39, and finally Miss Deans 1940 – 50. Filling the gaps were a procession of temporary postings, one of whom, Margaret Marren, 1939 – 40, wrote in depth in the Log, giving a vivid picture of the pupils, the weather, problems of travelling in by train, and ways of enlivening the curriculum.

Miss Marren was in charge when the 2nd World War was declared. The train service on which she relied was hit by ‘cuts’, which meant withdrawal of the afternoon train, causing her to stay on at school until 7.17 pm. The managers obligingly fixed the blackouts for the school so that she could work after dark by oil lamp, while awaiting her train. Thus she wrote copiously in the Log, with graphic description of the snow in early January and the problems of getting to and from the station with no discernible path. Others before her had had difficulty in reconciling the train times with the school opening hours. The teacher covering the last years of Mr Cooke’s 1st World War absence had travelled by train from the Morpeth direction, and was unable to arrive before 11am. Of this the visiting Inspector wrote: 'for a considerable period the school has been unfortunate in the arrangements of its staff…the responsible teacher lost much time through illness and to late arrival at school due to inconvenient train services. It is not surprising therefore that the work of the school fell into poor condition. When the present Master (Cpt Cooke) resumed he found no scheme of work and no records to assist him in planning the work necessary to improve the condition of the upper part of the school.'

Miss McKenna

The assistant teachers, in charge of the Infants, were without exception ‘uncertificated’, whereas the teacher in overall charge was always fully trained and qualified. One assistant teacher, Miss Annie McKenna, stands out, partly because of her long tenure, 1916 – 51, but also because of the affection in which she was held by those of us who remember her. She herself had been a pupil at Fontburn. She had moved to Rothbury, but returned to live at Whitehouse, renting a house in one of the rows built for quarry workers, most of whom had by that time moved away. She must have lent the school great continuity and hers was the face that welcomed us on our first day at school. She was kind, and generous with her time. What we may have lacked in rigour, we made up for in knowledge of ‘nature’ for she liked nothing better than to take us out for a nature walk, invariably ‘down the Dene’ (under the viaduct and into the valley) She most definitely was eccentric, but endearingly so and held in great affection by all who had passed through her care.

Miss McKenna and pupils, loaned by Lilian nee Eggleston

Click on picture for larger view

It is impossible to gauge our level of attainment under her tutelage. I can’t actually remember learning to read or to do number , but I do recall a bead counting frame and must have learnt these under her tutelage, so it must have been painless! In the HMI reports it was usually the Head who was taken to task, most references to the Infants being that there were too many of them and that room should be made for the older ones to move ‘up’ into the other room. On two occasions, following fairly damning reports, a ‘third’ assistant teacher was employed for the ‘Lower Mixed’, thus relieving the Infants teacher, Miss McKenna, of a burdensome crowd.

The Curriculum

My memories of any sort of routine curriculum are very hazy. We almost certainly would follow the sort of pattern laid down for the times. HMI Reports do give some insight, as they measured up their actual findings on the day of their visit against their expectations: just as happens today: nothing changes!

HMI Reports stressed aspects such as punctuality, attentiveness and accuracy in arithmetic and spelling. Music – singing – usually featured, and neatness of handwriting. Several times over the early years there were comments about indistinct speech, and the inability of the pupils to apply themselves when the teacher was not present. Often the teaching was considered too formal, but this improved under Mr Dixon, which makes this report of 1924 seem a little harsh: 'The children read fluently, and those in the highest class worked a test in Arithmetic very well. Other wise the general level of attainment is not what it ought to be.'

The defects pointed out in the report of 1922 still persisted: '1. the oral lessons are not effective. 2. the children’s written exercises are marred by bad handwriting and gross mistakes in spelling and punctuation. There is no reason why this should be so. A marked improvement will be expected when the school is next inspected.' Happily, 1925 was better, 'but the Head Master has a great deal to do before the work can be considered really satisfactory.' By 1926: 'There are many signs of a healthy endeavour in the conduct of this school, and criticisms that have been made on previous occasions are now being met.'

Considering the times and the daily obstacles that had to be met by the Head – isolation, no direct communication with the world outside, distances that the pupils had to travel, often extremely inclement weather, a building poorly heated by two stoves that were a perpetual problem, as was obtaining the co-operation of the first two caretakers, outside toilets, frozen pipes, and always the pressing question of attendance numbers – it is hardly surprising that some aspects of the learning did not rise to the Inspectors’ standards. Today we would call it ‘lack of stimulation’.

Class of unknown date, possibly 1935, loaned by Lilian

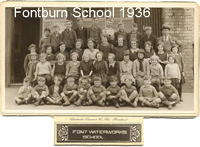

1936 school group, loaned by Jack Hepburn

Click on pictures for larger view

Miss Marren, ‘Supply’ Head in 1939 – 40, as war broke out, attempted to put this into words: 'Children in such an isolated district must in some manner be brought into contact with the outside world. I am attempting to supply this need by buying from my own private purse such well informed papers as The Times, Daily Telegraph, Morning Post, Yorkshire Post and Manchester Guardian so that children may have the benefit of suitable articles on home and foreign affairs and the many excellent maps and pictures produced. I have also ordered two copies of the ‘Children’s Newspaper’ to be delivered each week to the school.' The same teacher, when a telephone box was erected at Ewesley station, walked there with the senior pupils to inspect this new means of instant communication.

Christmas, Sports, Trips, Festivals and Celebrations

From early in its life, the school pupils had celebrated Christmas with a party. In later years this included gifts and money from the Orde family at Nunnykirk. Sports Day became an event that was clearly enjoyed, and in 1919 this was part of their ‘Peace Celebration’. The children were allowed to witness the eclipse of the sun in April 1921 using smoked glass and mirrors. Other departures from routine were infrequent but always noted: in the early period, frequent mention of cancelling school to visit Morpeth Music Festival; nature rambles with Miss McKenna; boys visiting the Whinstone Quarry at Whitehouse; Rothbury Maypole Fete, where the entire school travelled by train; a visit to Cragside; 1923, the King and Queen’s Empire message by gramophone recording (did the school have such a device?); 1930, a County Library van at Ewesley, where Miss McKenna was sent to choose books for the school.

1908 Medical Inspections begin

Fontburn school may have lacked a stimulating curriculum, but in other ways it more or less kept pace with national requirements. In 1908 along with all other state schools, the Annual Medical Inspection became a requirement and in 1909 Fontburn had its first set of medicals. This was part of a health drive to make the nation’s children fitter: children at risk were referred for further treatment and could be recommended for free milk and cod liver oil, though there is no record of this being applied at Fontburn. A visit from the school nurse became part of the annual calendar and the school dentist began visits in 1930. Under the ‘Milk in Schools’ scheme in 1936 children could purchase a third pint bottle of milk for two and a half (old) pence a week (approx. 1p today). There is no record of milk at Fontburn until 1947 when school milk became free for all school-age children: ours came in third-pint bottles from Roughlees Farm (Proctors). In the same year further ‘progress’ was made in terms of the widening Welfare State, when school dinners became available. Sandwiches or warming food through on the stove were no longer necessary. The eastern end of the Big room was partitioned off and cooking appliances, equipment and hot water installed. The boys’ cloakroom became the store room, and Mrs McLennan, one of the Fontburn mothers, became the first cook. We ate on oil-cloth covered tables at the back of the Big Room, and what substantial meals they were. Second or even third helpings were the norm, and for children who left home early, in the winter weather, this must have made a huge difference, not only to well being but also to the ability to stay alert through the school day. The Fontburn children had always been fortunate enough to be able to go home for a mid-day meal, but the novelty of meals on school premises was too good to miss. A sequence of Waterworks mothers took up the cook’s role, including Mrs Eggleston when Mrs McLennan scalded her feet, and finally my own mother, Mary Bewick, doubling up as cook and caretaker just before the school closed its doors in 1951.

Two World Wars

School had a role to play during both World Wars. In 1915, the children were encouraged to contribute to a penny fund to provide comforts for those at the front and the Christmas concert was in aid of the Soldiers’ fund. In 1916 children brought in eggs for wounded soldiers and these were despatched by train to a Central Committee for distribution. In 1917 it is noted that six dozen eggs were sent off, and the school becomes HQ of Fontburn and District War Savings Association. £80 worth of War Certificates purchased in the first month. The school garden was created growing a good yield of potatoes but had to be fenced to protect from sheep and rabbits. In 1918 the Red Cross appealed for nut shells and fruit stones for making charcoal respirators, though the Log does not comment on the outcome, possibly because of a lapse in Headship for a brief time, when there was quite a degree of ‘drift’ as noted by the HMI report in 1920. 11 November 1918 saw the Armistice, and the children were granted a long play that day followed by a holiday as thanksgiving. Subsequently a War Memorial was mentioned, and three past scholars named: Mark Richardson, William Rutherford and John Thomas Varnham. The scholars sang and marched past the Memorial. Based on knowledge of school in the 1940s, sadly, I have no recollection of this memorial, and can only wonder about it.

The Second World War saw not only the temporary Head Miss Marren trying to keep up to date with happenings in the outside world, but also superintending the erection of blackout at windows, and further development of the school garden. In 1940 gas masks were distributed – mine was a Mickey Mouse design – and school also oversaw distribution of clothing coupons. Gum boots, a gift from the women of Canada and USA, were given to all children who had a long distance to travel. I do not remember that, possibly because I would not qualify for any, but I do remember the Bring and Buy Sale in aid of Salute the Soldiers in 1944. School was closed to celebrate VE Day, thankfully bringing Fontburn School’s war experiences to an end. A very few evacuees had come and gone during the six years.

One of the evacuees was Ian, from Kent, whose mother was a friend of the McLennan family who themselves were then living at Blueburn. Mrs McLennan, nee Rutherford, had been born and bred near Whitehouse, and had brought her family back for safety. Ian recollects: 'towards the end of the war about 1944 when the rockets and the V1s started, the country went though a further evacuation and rather than go to a strange home my mother asked her friend Mrs McLennan if she would have me…hence the arrival of an evacuee from London, a real townie, to rural Fontburn – and I mean rural - what a shock for a 10 year old’s system… I then started school, joining Alison and Anthony (McLennan) and their Rutherford cousins. In the winter this seemed like a long journey, especially in deep snow. We all used to sit around a big stove and have our lessons – if you spat on the stove obviously when the teachers were not looking, it made a glorious hissing sound – I seem to remember lots of spitting going on when the teachers were absent, and of boots in the winter drying by the stove.’

In truth, for most of us, our childhood war experiences were slight and largely second-hand, related by those pupils who had come to live amongst us or who travelled in from Nunnykirk, where the Army had a base.

1944 Education Act

The 1944 Education Act was a watershed in the history of education, offering free and appropriate secondary

education to all, and using the 11+ exam as the yardstick for deciding children’s secondary destinations. No longer

were ‘through’ schools like Fontburn able to take pupils from infants right ‘through’ to school leaving age. Thus, the

more senior pupils left Fontburn for ‘secondary’ education, as of right. This was something that the pupils of

Fontburn had never known, for although schools that offered education beyond the Elementary stage had been

available right from the start, entry was by scholarship, which was neither free, nor very easily accessed by rural

pupils whose expectations from education were fairly modest. Prior to that time, movement beyond elementary to

grammar school in Morpeth was sparce. We know of Lance Smith in 1923 who passed for the King Edward VI's in

Morpeth, and Alice Stephenson and her sister in the 1930's, and in 1939 Hazel Hutton to Morpeth Girls’ High

School. In 1948 I was fortunate to pass the (for me) dreaded 11+ and so took up a place at Morpeth Girls High

School, travelling daily by train. Almost certainly, if this type of education had not by then become ‘free’, I would not

have been able to go, as my family could never have afforded to pay any fee or travel costs. As it was, my parents

had the greatest of difficulty in providing my uniform, partly because of the clothes rationing (coupons) but also

because we were so poor.

Other alternatives catering for 11-15 year olds were Brownrigg Camp School, near Bellingham and the ‘Modern’ school in Morpeth, at Mitford Road. Fontburn pupils used Brownrigg, which was residential, and as it was some distance from main public transport, pupils were given a special bus for arrivals and departures.

Closure

In many villages, the school is a space that is shared by the community for social as well as educational events. Fontburn was no exception, at least in the beginning. In 1906, it must have been used for a concert, and the Log entry reads as follows: 'Concert in school on Saturday last. As a result I found the desks with prints of boot nails and one desk covered in obscene writing. I make this entry lest the school children get the blame'. Six months later, it reads: 'Several of the desks are out of order as a result of constant moving for concerts and dances'. The following year: 'Entertainment in school last night. One of the desks is broken through standing on.' Not a very promising start, but it sounds as though the community were enjoying the amenity. No further mention is made of these events down the decades, which raises the question about any further use. From my own recollection, the school was used regularly for whist drives, especially in the 1940s, but not for concerts, or dances. At the end of the 2nd World War the party and dance held for the community VJ celebration was on Waterworks premises, in the hut that had formerly been the hostel then used as a workshop by Tom Bewick and Noel Eggleston. It was cleared and scrubbed out to make it habitable, and proved worthy of the occasion.

The remains of the school foundations in 1997

Photo M I Warren

The site of the school in 2007, under the hay feeder. Daffodils mark site of former school garden.

Photo M I Warren

Click on pictures for larger view

Even though the school may not have held as big a social role as it might have done, it was nevertheless a focal point for the community. Its passing in 1951 was symbolic of change away from life as we had known it. Miss Deans, who had led the teaching from 1940, had bravely fought illness but continued to travel from Thropton to Fontburn daily until only a few months prior to her death. The temporary Head wrote on 21 December 1951: 'I, E A Macgregor terminate my duties here today as Supply Head Teacher. From today Fontburn School will be closed permanently and the 17 children transferred to Rothbury.' My mother, who was by that time working as both caretaker and cook, was invited to choose a keepsake. She chose a picture, a painting of a vase of anemones, now bequeathed to me and near me as I write. It had been presented to the school in 1912 by Northumberland Education Department as a prize for good attendance. The school had been closed for a day, to celebrate. Ironically, it was now closed for ever.

Further Reading: Jenkins SC (1991) The Rothbury Branch , pub Oakwood Press

Website created by WarrenAssociates 2007

Website hosted by Vidahost

Copyright © Maud Isabel Warren 2008

www.Fontburnremembered.co.uk